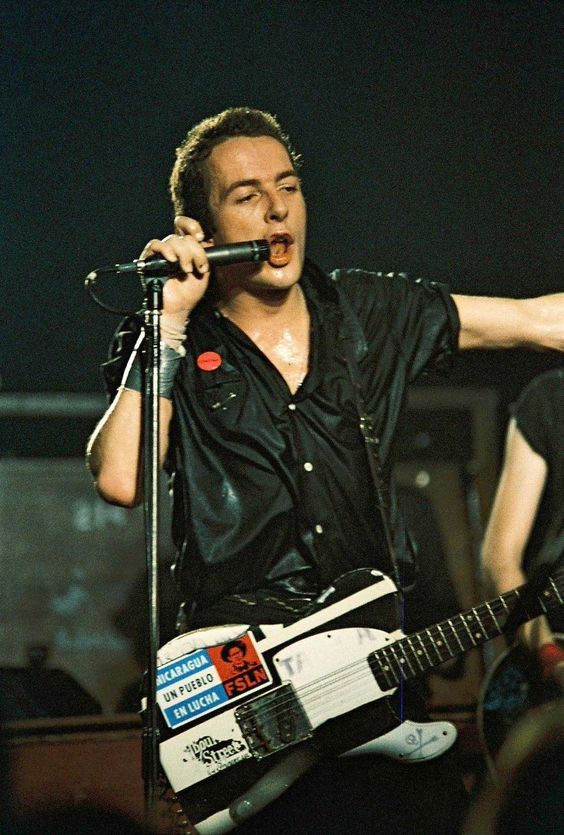

Toward the end of the Clash’s brilliant debut album there is the song, “Garageland,” the first line of which goes, “Back in my garage with my bullshit detector…” Apparently, Joe Strummer, who sang that song (with the accent on the first syllable of “garage,” so it rhymed with “carriage”), had a keen eye (or nose) for that aforementioned substance, and was conscientious about calling out its perpetrators. I think of poor Joe, who left us way too soon, whenever I come across meaningless, hifalutin’ writing.

A recent example: An agency client sent me a draft of a news release to edit. The boilerplate section of the release included the sentence, “We are pioneering prescription medicines.”

I immediately wondered, “What the hell is that supposed to mean?” One can design prescription medicines; one can develop prescription medicines; one can even improve or optimize prescription medicines. But “pioneer”? Please.

Still, I can imagine using “pioneering” in a sentence that was intended to convey that basic message, such as, “We are pioneering the intelligent design of prescription medicines,” or something along those lines. But I have trouble envisioning how one can “pioneer” a medication.

There is a word for writing that is meant to sound impressive but ends up being meaningless, and I think you know what it is. (Hint: It starts with a B and ends with T.)

Another recent example: Another agency client sent me a draft news release that included three suggested quotes for three different spokespersons. The first quote included the sentence, “Dosing of the first subject in this trial is an important milestone.” Three paragraphs down, another quote said, “Successful dosing of the first subject in this trial is a major event in the clinical development program for this promising product candidate.” Additionally, within the three quotes, there were two mentions of a high or significant “unmet medical need” — three words that are rapidly becoming one of the most hackneyed phrases in medical communications.

Just today, I was proofing some newsletter copy for another client. The newsletter article was an account of a pharma company’s team attending an advocacy conference. The article noted, “In addition to having the opportunity to present our data at the conference…”

Once again, I wondered, “What the hell?” Did they present their data at the conference, or did they not? If they did, why not say, “In addition to presenting our data at the conference…”? If they didn’t present their data, why mention that they had the “opportunity” to do so?

The three examples I’ve cited are hardly the most egregious I’ve come across over three decades in this business; they are merely the most recent to come to mind. But they have one thing in common: Each was written by a very bright, very talented, but very young (20-something) public relations professional. To be fair, I can imagine each of them becoming ever more conscious of their impending deadlines and their very demanding bosses, and feeling pressured to write something brilliant. Yet because of their limited experience and narrow frames of reference, the best they can come up with is hackneyed, repetitive prose.

That’s not their fault. If anyone’s to blame, it’s their supervisors. It’s up to us older folk, who (presumably) know better, to work closely with our younger colleagues and give them solid, constructive counsel. I know we all feel there’s not enough time in the day to accomplish everything on our to-do lists, but when bullshit copy sneaks out the door and lands in the client’s in-box, we all look bad.

(BTW, back in the day, I had the good fortune of seeing the Clash perform live — twice! — and those performances are among my favorite rock ‘n’ roll memories.)